Local Python Development Environment

Introduction

Some of my colleagues and friends had troubles setting up their local machines for working on Python projects. Things even got messier when there were multiple Python projects with different versions of packages or Python itself. Consequently, I’ve decided to write a small post that will serve as a quick guide and reference for those that are just starting with Python or switched from other programming languages and are not quite sure how things work in the Python ecosystem.

I hope this will help you, and please don’t hesitate to reach out with questions or suggestions!

Local Machine

This guide is primarily for unix-like systems. If you are using Windows, I suggest you use Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) or run a Docker image, which will allow you to experiment without breaking your OS environment.

The choice of OS shouldn’t matter. I’m running Manjaro on my personal PC, Ubuntu on work laptop, and a colleague is using the same setup on WSL-ubuntu.

Pyenv

Pyenv is a simple Python version management tool. It lets you easily switch between multiple versions of Python.

Installation

To install pyenv you can use

pyenv installer,

and run:

curl https://pyenv.run | bash

If the installation was successful, you’ll see the following message:

WARNING: seems you still have not added 'pyenv' to the load path.

# Load pyenv automatically by appending

# the following to

~/.bash_profile if it exists, otherwise ~/.profile (for login shells)

and ~/.bashrc (for interactive shells) :

export PYENV_ROOT="$HOME/.pyenv"

command -v pyenv >/dev/null || export PATH="$PYENV_ROOT/bin:$PATH"

eval "$(pyenv init -)"

# Restart your shell for the changes to take effect.

# Load pyenv-virtualenv automatically by adding

# the following to ~/.bashrc:

eval "$(pyenv virtualenv-init -)"

This will export PYENV_ROOT variable, add pyenv to the $PATH, and load

it automatically in a shell. After restarting your shell, the command

pyenv should output:

pyenv 2.3.7

Usage: pyenv <command> [<args>]

Some useful pyenv commands are:

--version Display the version of pyenv

activate Activate virtual environment

commands List all available pyenv commands

deactivate Deactivate virtual environment

doctor Verify pyenv installation and development tools to build pythons.

exec Run an executable with the selected Python version

global Set or show the global Python version(s)

help Display help for a command

hooks List hook scripts for a given pyenv command

init Configure the shell environment for pyenv

install Install a Python version using python-build

latest Print the latest installed or known version with the given prefix

local Set or show the local application-specific Python version(s)

prefix Display prefixes for Python versions

rehash Rehash pyenv shims (run this after installing executables)

root Display the root directory where versions and shims are kept

shell Set or show the shell-specific Python version

shims List existing pyenv shims

uninstall Uninstall Python versions

version Show the current Python version(s) and its origin

version-file Detect the file that sets the current pyenv version

version-name Show the current Python version

version-origin Explain how the current Python version is set

versions List all Python versions available to pyenv

virtualenv Create a Python virtualenv using the pyenv-virtualenv plugin

virtualenv-delete Uninstall a specific Python virtualenv

virtualenv-init Configure the shell environment for pyenv-virtualenv

virtualenv-prefix Display real_prefix for a Python virtualenv version

virtualenvs List all Python virtualenvs found in `$PYENV_ROOT/versions/*'.

whence List all Python versions that contain the given executable

which Display the full path to an executable

Python versions

It’s important to mention that pyenv builds python from source, which means

that we’ll need some library dependencies installed before we use it.

Dependencies will vary depending on your OS. If you are using Ubuntu:

apt-get install -y make build-essential libssl-dev zlib1g-dev \

libbz2-dev libreadline-dev libsqlite3-dev wget curl llvm libncurses5-dev \

libncursesw5-dev xz-utils tk-dev libffi-dev liblzma-dev python-openssl

Now that we have everything that we need, we can build a Python version,

for example 3.10.4:

pyenv install 3.10.4

If that worked, you can list installed versions using:

> pyenv versions

* system (set by /root/.pyenv/version)

3.10.4

As you can see, we are using the system’s Python version. To set 3.10.4 as a

global Python version use pyenv global 3.10.4, and check python -V to

ensure that the version is correct.

If you run

which python, you’ll see an interesting path<something>/.pyenv/shims/python. Thisshimsdirectory is inserted at the front of your$PATH(check withecho $PATH) and it’s a directory to match every Python command across every installed version of Python.pyenvbasically maintains lightweight executables that pass python commands along topyenv.

If we have multiple versions and want to set a specific version on a folder

level, we can use pyenv local, for example pyenv local 3.9.15. This will

create a file .python-version which basically tells pyenv which version to

use. It also works for subdirectories.

Poetry

Alright, now that we can control multiple Python versions on our system. How to approach the scenario with multiple projects with different package versions?

The idea is to create a separate environment for each project so that dependencies for one project have nothing to do and don’t collide with dependencies for other projects. This is done through a virtual environment.

Python already has its built-in

venvmodule for creating virtual environments. To create a virtual environment usepython -m venv /path/to/new/virtual/environmentand then activate it. See venv for more information. However, there are tools like Poetry and Pipenv that manage that for you.

Tools like Poetry not only manage virtual environments but also handle dependencies that can help us manage projects in a deterministic way.

If you had experience with JavaScript, you can think of Poetry as npm.

Template

To start with Poetry, we can create a new project using

poetry new <project-name>, for example: poetry new test-app.

This will create a basic boilerplate as a starter for any Python project.

This boilerplate includes:

testsfoldertest-appfolderREADME.rstfilepyproject.tomlfile

pyproject.toml is basically a file that defines the project:

[tool.poetry]

name = "test-app"

version = "0.1.0"

description = ""

authors = ["Vladsiv <email>"]

[tool.poetry.dependencies]

python = "^3.7"

[tool.poetry.dev-dependencies]

pytest = "^5.2"

[build-system]

requires = ["poetry-core>=1.0.0"]

build-backend = "poetry.core.masonry.api"

The first section [tool.poetry] defines general information about the

package: name, version, description, license, authors, maintainers,

keywords, etc.

The second section [tool.poetry.dependencies] defines production

dependencies. If you build a package wheel, it will include only production

libraries as dependencies.

The third section [tool.poetry-dev-dependencies] defines development

dependencies. As you can see in the example, it specifies the version for

pytest, which is a library for writing tests. We don’t need that for

production environment.

The forth section [build-system] is a

PEP-517

specification that is used to define alternative build systems to build a

Python project. In other words, other libraries will know that your project

is managed by Poetry.

Environment

Now that we have a new Python project with some boilerplate code, let’s run

poetry env info. This command give us some information about the project’s

environment. Output looks something like:

Virtualenv

Python: 3.7.12

Implementation: CPython

Path: NA

System

Platform: linux

OS: posix

Python: /home/vladimir/.pyenv/versions/3.7.12

As we can see, we are using Python version managed by pyenv. However, for

the virtual environment path we have NA, which tells us that our project does

not have an environment.

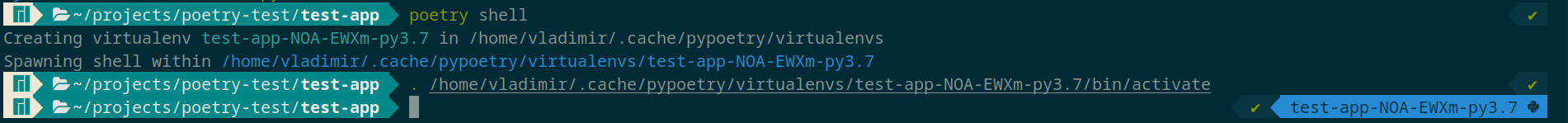

To create it, we can use poetry shell. It will create a virtual environment if

it doesn’t exist and activate it. In terminal it looks like:

The first line says that it’s creating an environment in

/home/vladimir/.cache/pypoetry/virtualenvs. This is the standard location for

all virtual environments managed by Poetry. If you want to delete

an environment and recreate it, just go to that path, run rm -rf <env-folder>,

and create it again using the same poetry command.

If you take a closer look at the image, you’ll see the environment name on the right hand side (in blue). That’s automatically added to the terminal line using a zsh theme. If you want a lit terminal, see romkatv/powerlevel10k.

Since we activated a virtual environment, we can run poetry env info again

to confirm the setup:

Virtualenv

Python: 3.7.12

Implementation: CPython

Path: /home/vladimir/.cache/pypoetry/virtualenvs/test-app-NOA-EWXm-py3.7

Valid: True

System

Platform: linux

OS: posix

Python: /home/vladimir/.pyenv/versions/3.7.12

This is the setup that we want, pyenv manages python versions and Poetry

takes care of virtual environment and packages. Using this approach, we can have

multiple projects running on different Python versions in a completely isolated

virtual environments.

Dependencies

There is another really important file: poetry.lock. This file is used to

specify exact versions and hashes of packages that are used as dependencies. If

you look at our test-app project folder, we don’t have it. This is because we

haven’t installed anything yet. To install dependencies, use poetry install:

Updating dependencies

Resolving dependencies... (2.6s)

Writing lock file

Package operations: 10 installs, 0 updates, 0 removals

• Installing typing-extensions (4.4.0)

• Installing zipp (3.11.0)

• Installing importlib-metadata (5.1.0)

• Installing attrs (22.1.0)

• Installing more-itertools (9.0.0)

• Installing packaging (22.0)

• Installing pluggy (0.13.1)

• Installing py (1.11.0)

• Installing wcwidth (0.2.5)

• Installing pytest (5.4.3)

Installing the current project: test-app (0.1.0)

In this case it installs pytest, its dependencies, and creates a poetry.lock

file. At the bottom of the poetry.lock you’ll find sha hashes of package

wheels which allows exact recreation of a virtual environment across multiple

machines from development to production.

Use poetry add <package> to add a new package dependency, for example

poetry add requests:

Using version ^2.28.1 for requests

Updating dependencies

Resolving dependencies... (5.1s)

Writing lock file

Package operations: 5 installs, 0 updates, 0 removals

• Installing certifi (2022.12.7)

• Installing charset-normalizer (2.1.1)

• Installing idna (3.4)

• Installing urllib3 (1.26.13)

• Installing requests (2.28.1)

This will update poetry.lock but also pyproject.toml, which now

specifies requests as a production dependency:

[tool.poetry.dependencies]

python = "^3.7"

requests = "^2.28.1"

If we want a development dependency use poetry add <package> --dev, this

will add the package to [tool.poetry.dev-dependencies] section.

Scripts

Poetry offers a way to run scripts using poetry run <script-name>. This is

especially useful for CICD pipelines where we can define scripts for various

things, such as tests, linters, building, deploying, etc.

Simple Function

The simplest way is to create a folder scripts that acts as a module of

functions, for example build.py which has build_documentation function.

Then in pyproject.toml create the [tool.poetry.scripts] section:

[tool.poetry.scripts]

build-documentation = "scripts.build:start"

Click

Personally, I like the setup with click. It offers elegant solutions for building CLI tools.

Add it as a development dependency: poetry add click --dev, and create

the following structure under scripts folder:

scripts/

├─ __init__.py

├─ cli.py

├─ build.py

├─ linters.py

├─ tests.py

└─ deploy.py

Where the cli.py looks like, for example:

import click

from scripts.build import build_documentation, build_package, build_wheel

from scripts.deploy import deploy_to_aws, deploy_to_azure

from scripts.tests import test_integration, test_package

from scripts.linters import run_pylint, run_mypy

@click.group()

def build():

pass

@click.group()

def tests():

pass

@click.group()

def linters():

pass

@click.group()

def deploy():

pass

@build.command()

def package():

build_package()

@build.command()

def wheel():

build_wheel()

@build.command()

def wheel():

build_documentation()

@deploy.command()

def aws():

deploy_to_aws()

# ...

Then in pyproject.toml specify the scripts:

[tool.poetry.scripts]

build = "scripts.cli:build"

tests = "scripts.cli:tests"

deploy = "scripts.cli:deploy"

linters = "scripts.cli:linters"

This allows you to use all the nice CLI features that click provides, both

in local development and CICD scripts.

Pytest

Pytest is a framework for writing python tests. It has a lot of features that allow us to write complex and scalable functional tests for applications and libraries. Additionally, pytest supports third-party plugins that offer additional functionality - How to install and use plugins.

Pytest’s documentation and how-to guides are extensive and well-written, especially when it comes to fixtures. If you are not familiar with fixtures and how to use them, please go through How to use fixtures.

There are two plugins that I consider essential:

- pytest-cov - Takes care of coverage reports. Basically, it checks how well an application is covered with tests. It is especially valuable in CICD pipelines. If a developer pushes new code, you want to make sure that each new line is covered with tests. So if coverage is not 100%, pipeline should fail with a detailed report.

- pytest-xdist -

Takes care of parallel testing. As application grows, the number of tests and

time it takes to run them significantly increases. Performance of test suites

can directly impact cost and time spent for development. For example, if you

are running CICD pipelines on GitLab that uses EC2 or Fargate instances on AWS.

Essentially, you are paying for X number of CPUs, but running tests only on one.

This plugin extends pytest with additional modes that allow it to distribute

tests across multiple CPUs to speed up test execution. Additionally,

pytest-covalso works withpytest-xdist.

Pylint

Another tool that’s essential for python projects is pylint. It’s a library that provides a python linter.

If you are not sure what a linter is, please see What is a linter and why your team should use it?

Pylint runs through the source code without executing it (static analysis) and checks for potential bugs, performance issue, coding style misalignments, poorly designed code, code smells, etc.

It supports extensions, plugins, and extensive configuration which you can use to enforce some of the projects requirements and coding styles.

MyPy

MyPy is another type of tool that checks your code for potential bugs. It is an optional static type checker for Python.

Using it we can combine the benefits of both duck and static typing. For example the following code (example from the MyPy’s documentation):

def fib(n):

a, b = 0, 1

while a < n:

yield a

a, b = b, a+b

Can be statically typed as

def fib(n: int) -> Iterator[int]:

a, b = 0, 1

while a < n:

yield a

a, b = b, a+b

Apart from bug checking, this tool can greatly improve maintenance of the project and serve as a machine-checked documentation. If you are just starting out with MyPy, check this awesome guide: The Comprehensive Guide to mypy.

Leave a comment